The Yayoi period (300 BC - 250 AD): a pivotal era in Japanese history

- Published on : 31/03/2024

- by : S.R.

- Youtube

The Yayoi period, from around 300 B.C. to 250 A.D., was a major transitional phase between the Jômon period that preceded it and the Kofun period that followed. Marked by profound changes and decisive advances, this era saw ancient Japan enter the metal age and adopt rice cultivation, paving the way for the emergence of classical Japanese civilization. Let's delve into the heart of this fascinating period to discover its key moments and main characteristics.

Origins and chronology of the Yayoi period

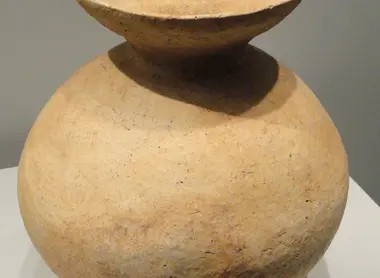

The name "Yayoi" comes from the district of Tokyo where the first pottery typical of this period was unearthed in 1884. Japanese archaeologists have since refined the dating and subdivided the period into several phases: Initial Yayoi (900-400 BC), Ancient (400-200 BC), Middle (200 BC - 50 AD) and Final (50-250 AD). While the beginning of the period is still a matter of debate, specialists agree that the transition from Jômon to Yayoi began gradually around 900 B.C. in northern Kyushu, before spreading to the entire archipelago.

An agricultural and technological revolution from Korea

Continental influences and contributions, particularly from the Korean peninsula, played a decisive role in the transformations of the Yayoi period. Among the major innovations introduced from Korea was flooded rice cultivation, which led to unprecedented yields and food production. Cultivated in rice paddies irrigated by a system of canals, rice became the staple food. Wheat, barley, millet and soya were also developed. At the same time, the archipelago saw the arrival of bronze and iron technologies, again probably transmitted by Korean migrants from the Mumun culture who settled in northern Kyushu. Initially used for weapons and ritual objects, bronze was gradually supplanted by iron for toolmaking.

Reconstruction of the Yayôi village on the Yoshinagari site

Wikipedia

Changes in habitat, pottery and tools

The adoption of agriculture led to changes in lifestyles and housing. Villages became larger and more permanent, with raised wooden houses housing up to 6 people. Granaries on stilts are used to store harvests. Some agglomerations, such as the Asahi site in today's Aichi prefecture, can cover up to 80 hectares and are considered regional centers. Yayoi pottery, less ornate than Jômon but more functional, is characterized by large necked jars, bowls and wide-mouth pots. At the same time, lithic tools inherited from Jômon were perfected with polished stone blades. Lacquer and weaving also made their appearance.

The rise of trade and the emergence of a hierarchical society

In contrast to Jômon, the Yayoi period saw the development of trade and exchange, both between communities in the archipelago and with the mainland. Raw materials, finished products and prestige goods circulated over long distances. At the same time, society became stratified and hierarchical, with local chieftaincies controlling the best land and trade. Around a hundred "countries" or confederations of clans are attested at the turn of our era. The appearance of weapons and fortifications also suggests a period of conflict between rival entities seeking to extend their territorial hold.

Funeral practices and beliefs of the Yayoi period

Mortuary practices reflect growing social stratification. Graves were differentiated according to the person's status: simple jar-cercules for the common man, imposing dolmens for chieftains. Funerary furnishings, made up of weapons and bronze or iron ornaments, also became a social marker. Beliefs of the period remain difficult to pin down, but the ritual role of large bronze objects such as Dotaku bells or ceremonial weapons attests to a religious system in full evolution, perhaps with agrarian rites and cults linked to ancestors and the authority of chiefs.

Relations with China and mention of the Wa in Chinese chronicles

Chinese chronicles from the Han and Wei dynasties are the first written sources to mention Japan in this period under the name "Wa" (倭). The earliest reference dates from 57 AD and mentions the sending of missions and tributes to the Chinese commanderies in Korea. A text from 297 speaks of 100 Wa "countries" or chiefdoms, including the powerful kingdom of Yamatai ruled by the queen-chamane Himiko. Although these accounts must be treated with caution, they confirm the development of relations with China and the existence of proto-state structures at the end of the Yayoi period.

The legacy of the Yayoi period in Japanese history

The joint introduction of agriculture, metallurgy, a stratified society and the first states during the Yayoi period laid the foundations for classical Japanese civilization, which would flourish over the following centuries. Japanese history would never be the same after this decisive turning point. Thus, through the successful synthesis of continental influences and indigenous substratum, the Yayoi men laid the foundations of an original culture destined for tremendous influence. In many ways, the foundations of Japanese identity are rooted in the fertile crucible of this pivotal period. To return to Yayoi is to go back to the very roots of what makes Japanese civilization so unique and great.