Sôhei the soldier-monks: the history and impact of Buddhist warriors in medieval Japan

In the heart of medieval Japan, a unique figure emerges: the sôhei, or soldier-monk. These Buddhist warriors, at once men of faith and formidable fighters, have profoundly marked Japanese history. Combining spirituality and the art of warfare, the sôhei played a crucial role in the religious and political conflicts that shook the archipelago for centuries. From their origins in the 10th century to their decline in the 16th, their history reflects the turbulence of a pivotal era. Let's discover together the fascinating history of these warrior-monks, their organization, their fighting techniques and the legacy they have left on Japanese culture.

Origins and emergence of sôhei in the 10th century

The first soldier-monks appeared in 10th-century Japan, against a backdrop of rivalry between different branches of Buddhism. This phenomenon had its origins in tensions between two branches of the Tendai sect, both based in the town of Otsu on Mount Hiei. The Enryaku-ji and Mii-dera temples, each representing a branch of this sect, were at the heart of these conflicts.

The birth of the sôhei is closely linked to the need for the great monasteries to protect their vast territorial holdings, known as shōen. These domains were veritable fiefdoms, from which the temples drew substantial resources in the form of taxes. To defend these interests, monasteries began training monks in the martial arts, creating a new category of religious: soldier-monks.

Over time, other major temples such as Tôdai-ji and Kôfuku-ji in Nara also formed their own sôhei groups. The phenomenon gained momentum in the 11th century, with more and more troops taking part in increasingly violent conflicts. These clashes were often motivated by issues of power, such as the appointment of a rival as head of a neighboring temple.

Organization and role of sôhei in religious and political conflicts

The sôhei were organized into large groups or armies within their respective monasteries. The most famous of these was Enryaku-ji, located on Mount Hiei overlooking Kyoto. The soldier-monks of Enryaku-ji were known as yama-hōshi or yama-bōshi, meaning "monks of the mountain". This name underlines the symbolic and strategic importance of Mount Hiei in the Japanese imagination of the time.

The role of the sôhei went far beyond simply defending the monasteries. They had become key players in the political and religious life of medieval Japan. Their influence was such that they could sometimes force the daimyō (feudal lords) to collaborate with them, or even occupy the imperial capital when they disliked the emperor's decisions. This ability to influence the country's affairs illustrates the considerable power acquired by certain Buddhist monasteries.

Conflicts between Buddhist temples were frequent and often violent. An emblematic example is the burning of the Mii-dera by monks from Enryaku-ji in the mid-12th century, marking the height of violence between these two rival institutions. These clashes reflected not only religious disagreements, but also struggles for power and influence in a changing Japan.

Equipment and fighting techniques of the warrior-monks

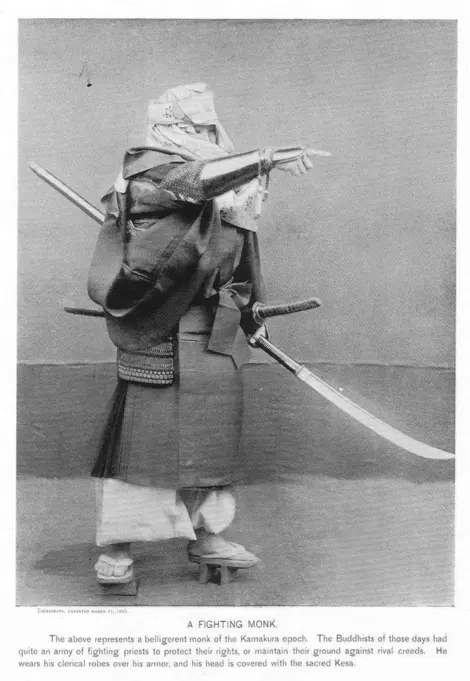

The sôhei used a variety of weaponry, adapted to their dual status as monks and warriors. Although the naginata (a type of Japanese halberd) is the weapon most often associated with them, many warrior-monks wielded a wide variety of weapons, from bows and staffs to swords.

Their battle dress was equally distinctive. The sôhei usually wore a stack of kimono-like robes, with a white robe underneath and a beige or saffron-yellow robe on top. This outfit, which had changed little since the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in the 7th century, was complemented by traditional footwear such as tabi (socks) and geta or waraji (sandals). For protection, many also wore various types of samurai armour.

The fighting techniques of the sôhei were formidable. They were accomplished warriors, mastering sword fighting, horseback riding and archery. Their emblematic weapon, the naginata, enabled them to effectively keep their opponents at a distance. In addition, they were trained to wield the kanabō, a large steel club or staff, used to defeat an opponent without spilling blood, in accordance with Buddhist precepts.

The heyday of the sôhei during the Gempei War (1180-1185)

The Gempei War, fought between the Minamoto and Taira clans between 1180 and 1185, marked the apogee of the sôhei's influence. This major conflict in Japanese history was an opportunity for the soldier-monks to emerge from their internecine wars and influence the country's destiny. The two rival clans sought to ally themselves with the powerful troops of soldier-monks, aware of the considerable impact they could have on the battlefield.

A famous episode in this war involving the sôhei is the First Battle of Uji in 1180. In this confrontation, Mii-dera monks, allied with the Minamoto, attempted to defend the bridge over the Uji River against Taira forces. The monks removed the bridge planks to prevent enemy cavalry from crossing, and valiantly held their position with bows, naginata, sabers and daggers. Although they were eventually defeated, their fierce resistance illustrates the power and determination of the sôhei.

The Gempei War also saw the emergence of legendary figures among the soldier-monks. One of the most famous is the monk Benkei, companion of the great samurai Minamoto no Yoshitsune. Benkei has entered Japanese legend for his many feats of warfare and his unwavering loyalty to his master. His story of superhuman strength and absolute devotion embodies the ideal of the warrior-monk in the Japanese collective imagination.

The evolution of sôhei: from ikkô-ikki to their decline in the 16th century

After the Gempei War, there was a relative lull in sôhei activity. However, the warrior-monk phenomenon underwent a new evolution with the emergence of the ikkô-ikki during the Sengoku period (1477-1573). The ikkô-ikki, literally "one direction, one category", were warrior leagues made up of men from the peasantry, the nobility, Buddhist monks and Shinto priests, driven by an ardent faith and egalitarian demands.

These new formations, although inspired by the heritage of the sôhei, differed in their more heterogeneous composition and their more social and political objectives. The ikkô-ikki often opposed the authority of the daimyô and samurai, seeking to establish a more egalitarian form of social organization. At the height of their power, they were able to resist the future great unifiers of Japan, such as Oda Nobunaga and Tokugawa Ieyasu, on their own lands.

However, the rise of the great warlords sounded the death knell for the warrior-monks. Oda Nobunaga, in particular, led a ruthless campaign against the strongholds of the ikkô-ikki. In 1571, he destroyed the Enryaku-ji, putting an end to centuries of domination by this temple over the political and religious life of Japan. The sieges of Nagashima (1571-1574) and Ishiyama Hongan-ji (1570-1580) marked the end of the military power of the religious leagues.

Heritage and representations of sôhei in Japanese culture

Although their era is over, the sôhei have left an indelible imprint on Japanese culture and imagination. Their history, blending spirituality and the art of warfare, continues to fascinate and inspire. Warrior-monks have become recurrent figures in Japanese literature, theater, film and visual arts, often symbolizing the duality between the spiritual quest and the brutal reality of the world.

In contemporary popular culture, sôhei appear frequently in manga, anime and video games. Their image oscillates between that of fearsome warriors and powerful spiritual figures, reflecting the complexity of their historical heritage. Characters like Benkei continue to embody the ideal of the loyal, powerful warrior, deeply rooted in Japanese martial tradition.

The heritage of the sôhei can also be found in certain modern martial practices. Although the warrior-monks have disappeared as a military force, their influence lives on in the holistic approach of certain Japanese martial arts, which seek to combine spiritual development with technical mastery. Their history recalls the complex relationship between religion and politics in medieval Japan, and continues to fuel reflections on the role of spirituality in a constantly evolving society.

Ultimately, the story of the sôhei offers a fascinating glimpse into a time when faith and combat were intimately linked. Their journey, from their emergence in the 10th century to their decline in the 16th, reflects the profound transformations that Japanese society underwent during this tumultuous period. Today, their legacy continues to intrigue and inspire, reminding us of the complexity of Japanese history and the richness of its culture. Follow in the footsteps of legend with a tailor-made tour !