Kyoto Machiya

- Published on : 25/12/2012

- by : Japan Experience

- Youtube

Kyoto Machiya are the town houses once favored by Kyoto's merchant class. Long neglected, Kyoto's machiya are now enjoying a "boom" in popularity.

Kyoto Townhouses: Machiya

The use of wood is one of the hallmarks of Japanese architecture, past and present.

In Kyoto, in particular, wood retains a special place in the often garish pantheon of modern Japanese building.

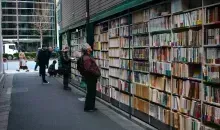

Tucked in between pachinko and karaoke parlors, "game centers" and just plain ugly mass-produced homes and "mansions," Kyoto is still home to many beautiful examples of the best of Japanese building.

These include the well-known temples and shrines, and the few remaining villas left in Kyoto. Added to this list would also be machiya (literally, town house; a typical downtown home is pictured above right).

Kyoto's machiya can be seen scattered around the city though the Sanneizaka area near Kiyomizudera Temple in eastern Kyoto retains a high percentage of the original buildings.

Kyoto machiya in the central district of the city

Machiya Architecture

From the Edo Period (1600-1868) onwards, machiya served as the residence and place of business for merchant families, who, according to the strict and myriad laws of the Tokugawa regime, were forbidden to openly display any sign of prosperity or ostentation.

Machiya are generally narrow at the front and extending way back from the street. This is because taxes were levied on houses in proportion to the width of the frontage during the Edo Period, a law which was circumvented by building away from the street.

The fronts of machiya in Kyoto have certain interesting design features such as komayose, a wooden railing, and inuyarai, a "dog barrier" made from curved bamboo slats. These barriers originally served the purpose of stopping beggars from sitting against the walls and keeping the houses from being soiled by dogs or splashed with mud by passing vehicles. Now, their function is largely to conceal air-conditioning units.

The windows of machiya are covered by slatted wooden frames called koshi or senbon-goshi ("thousand slat lattice"), which were fitted to try to gain some privacy from the street directly outside. There are various designs of latticework according to the type of premises. Other windows are usually covered by bamboo blinds called sudare.

Cafe housed in a machiya, Kyoto

Kyoto Machiya Survive World War II

Spared most of the bombing during World War II, Kyoto was the only major Japanese city that was left intact.

However, in the 1950's and 1960's Kyoto began in earnest to dismantle its cityscape in pursuit of something more "modern." Still, unlike Tokyo and Osaka - and nearly every major Japanese city - Kyoto was not bombed to the ground. Today there is even a "boom" in refurbishing and converting older wooden buildings.

These are primarily but not limited to machiya, the old townhouses that were favored by Kyoto merchants in the pre-War period.

Until recently, they were looked down on as kurai, which literally means dark. However, it has a negative connotation that would include poor, cold, uncomfortable, even medieval.

From the post-War period until today, these homes routinely were knocked down - by those who could afford to - and replaced by modern, plastic, disposable, soulless pseudo-Western structures. For those who could not, they were a mark of poverty and shame.

Machiya Redevelopment & Restoration Projects

Though downtown Kyoto has seen a repopulation thanks mainly to the increase in "mansions" - tower apartments - and the convenience of living within walking distance of restaurants and subways and trains, there has been an accompanying reappraisal of machiya.

Several groups have spung up with the avowed purpose of "saving Kyoto," or "saving machiya." Among them are Mitate, which is primarily made up of college professors and foreign residents of Kyoto, and Kongo no Kyomachiya no Hozen/Saisei no arikata Kento kai (The Committee Dedicated to Preserving and Renewing Kyoto Machiya for the Future), a group that is sponsored by the Kyoto metropolitan government.

Riverside Kyoto machiya in the Gion district of the city.

The powers that be have at long last realized that there is money to be made out of historic preservation, and appear genuine in their effort at keeping at bay the ubiquitous wrecking ball.

In addition to municipal efforts, a group of local carpenters and architects, plasterers and thatchers formed the Kyomachiya Sakujigumi in 1999, and will inaugurate a two-year program beginning April, 2006, to pass on traditional building and design techniques.

Machiya are now being converted into boutiques (see below), high-end restaurants, galleries, and other ambitious projects by both locals and also money from Tokyo. And it is the money that has made the city sit up and notice.

According to city survey conducted in 1998, there were approximately 28,000 machiya in the downtown area of Kyoto.

In a similar survey conducted in April, 2004, that number had fallen by 13%. Among the reasons for tearing down a machiya, polled residents gave the following: upkeep, not earthquake resistant, vulnerability to fire, etc.

In response the city has drawn up plans to alleviate the above concerns. Hopes are that the national government will also help in the effort at making Kyoto less unattractive - and help in preserving some of the best of the city's culture.

Interview with Master Machiya Builder Yasuyuki Nako (coming soon)