Battle of Fushimi Toba

Japanese History: read an account of the Battle of Fushimi Toba, south of Kyoto. The Battle of Fushimi Toba was a decisive victory for Imperial forces over the Tokugawa Shogunate army.

Japanese History: Battle of Fushimi Toba 鳥羽・伏見の戦い

by Philippa Bacon

The large pachinko parlor, cut-price electronics store and garish pro-diving shop on a busy intersection of Route 1 from Kyoto to Osaka hold few discernible traces of the past. Only the name, Akaike or 'Red Pond' gives any clue to the bloody history of this place in Fushimi-ku, near the banks of the Kamo and Katsura rivers in south Kyoto just below the Meishin Expressway.

It was here in the winter of 1868 that the future course of Japan's modern history was ultimately decided in a four-day battle, which saw the defeat of the last Shogun's armies, by the combined forces of Satsuma (modern-day Kagoshima prefecture) and Choshu (Yamaguchi). 500 men lost their lives and nearly 1500 were wounded in the 'Red Pond' - the Battle of Fushimi-Toba (also known as the Battle of Toba-Fushimi).

The two armies that faced each other on a cold, sunny 27 January 1868 represented the opposing forces vying for control of the country in the wake of the complex economic, political and social changes that had been occurring over the past fifteen years. These changes had been triggered by the need for a vibrant response to the arrival of the confident, industrialized and aggressive Western powers off Japan's coast in the shape of Commodore Perry and an American flotilla at Shimoda in 1853.

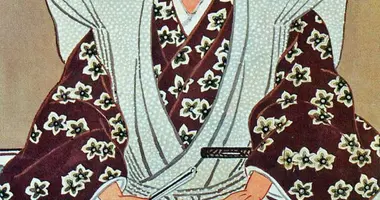

Satsuma samurai at the time of the Bakumatsu

Satsuma samurai at the time of the Bakumatsu

Present-day Fushimi Castle, Kyoto

Present-day Fushimi Castle, Kyoto Fushimi Castle, Kyoto

Fushimi Castle, Kyoto

Since Perry's arrival internal division and strife had wracked the nation. Acts of violence and terrorism directed against both officials of the Tokugawa shogunate and foreigners had resulted in a serious of armed conflicts.

So-called men of action or 'shishi' who blamed the weakness of the shogun for allowing foreigners access to the newly-opened 'treaty ports' congregated around the Imperial seat in Kyoto, which became a hot-bed of political intrigue, opposition to the shogun and sporadic violence.

These dramatic events were set against a long-term downturn in the by now moribund economy exposed for the first time to international capitalism and a general feeling of resentment directed at the established order in both the national and han (domain) governments.

The merchant class, deprived of social rank and privilege, was unhappy at financing the increasingly unproductive samurai and peasant uprisings increased in the period in response to local famines and hardship. Japan, at the time, was a powder-keg waiting to explode.

The Tokugawa shogun's forces, in a sense, represented the old established order, whose policies of seclusion and social control were blamed for failing to keep the Western 'barbarians' at bay.

Correspondingly, Satsuma and Choshu represented the modernizers who sought to destroy the shogunate and replace it with a more unified system under the symbol of a 'restored' Emperor.

This simplified distinction between old and new, feudal and modern could be seen to a certain extent in the armies that faced off on the river banks and flood plains that served as the main arteries into the old capital.

The Tokugawa forces were a mishmash of traditional samurai pikemen and cavalry as well as French-trained rifle companies. The British diplomat, A. H. Mitford's description of this army on reaching Osaka captures well its anachronistic nature.

"A more extravagantly weird picture it would be difficult to imagine. There were some infantry armed with European rifles, but there were also warriors clad in the old armour of the country carrying spears, bows and arrows, curiously shaped with sword and dirk, who looked as if they had stepped out of some old pictures of the wars in the Middle Ages. Hideous masks of lacquer and iron, fringed with portentous whiskers and mustachios, crested helmets with wigs from which long streamers of horsehair floated to their waists, might strike terror into any enemy. They looked like the hobgoblins of a nightmare."

On 26 January these troops, about 13,000 men, advanced from Osaka along the Yodo river to attack their enemies in Kyoto and were met by a very different army, dug into well-prepared positions in the villages of Toba and Fushimi.

Chosu Kiheitai Troops in a Contemporary Photograph

Chosu Kiheitai Troops in a Contemporary Photograph

Satsuma & Chosu

These opponents, around 6,000 men from mainly Satsuma and Choshu, were organized into rifle companies on the Western model, wore Western-style uniforms and included men from all segments of society as opposed to the purely samurai troops of the Tokugawa.

In addition the Satsuma-Choshu troops were battle-hardened veterans of previous clashes with Tokugawa and Western soldiers, gained promotion on merit and were led by experienced commanders, such as the young Saigo Takamori. They also had the best of the weather with a bitterly cold wind blowing at their backs.

Moreover, the Sat-Cho men were armed with cannon and Minie and Spencer rifles as well as a Gatling gun, products of the nineteenth century industrial West, a society on a completely different technological level to late "feudal" Japan.

These French and American rifles were more accurate, had greater range and could be reloaded quicker than the old blunderbusses of the Tokugawa troops who possessed only a few Minies in the hands of their French-trained detachments.

Contemporary print of the Battle of Fushimi-Toba

Contemporary print of the Battle of Fushimi-Toba

Battle Begins

Hostilities commenced suddenly and unexpectedly at around 5 p.m. on 27 January, first at Toba (present day Akaike intersection) and then at nearby Fushimi as the Tokugawa forces were refused entry into the city. Rifle fire 'like rain' fell on the mainly Shinsengumi pikemen and Aizu (Fukushima) swordsmen until the Tokugawa army withdrew to Yodo castle (near the modern racecourse) around midnight.

The shogun's forces had not been expecting an attack as it was so late in the day and had not brought up all their best men and artillery. As they fled they set fire to nearby houses and thus made themselves easy targets in the firelight.

The second day of fighting was more of a stalemate with the fighting raging up and down the roads on the banks of the Katsura and Uji rivers. The third day proved decisive with the Tokugawa forces driven back by cannon and rifle fire to the gates of the castle at Yodo, whose defenders, vassals of the daimyo of Yodo, sensing the way the battle was going, effectively changed sides and refused entry to the tiring Tokugawa troops, who now had no alternative but to retreat towards Yawata and Hirakata.

On the fourth and last day of conflict the Sat-Cho troops crossed the Kizu river in small boats to attack Yawata and were aided by the treachery of men from Tsu (Mie) who by secret agreement had changed sides and fired on their erstwhile allies, the Tokugawa army, which now pulled back in disarray to Hirakata and then on to Osaka. The old order had fallen.

Western interest in the unfolding and confusing events was keen. Two mounted French military observers were present at the scene of the hostilities in Yodo watching the progress of the Tokugawa forces they had helped to train.

Foreign Reaction

The latter-day foreign community in Kansai, (Americans, British, Dutch, Prussians, French, Danes and Italians) were gathered in Osaka where the fires started in the confrontation at Fushimi could be clearly seen as a vast red glow in the sky.

The Western community was anxiously awaiting developments and ready to evacuate to their warships if the victors proved aggressive. This scenario seemed likely when foreigners were shot at in Kobe by troops from Bizen (Okayama) in early February and eleven French sailors were killed in the so-called Sakai Incident in Sakai a port town, south of Osaka by a group of Tosa (Kochi) samurai.

However, in the meantime, representatives of the new regime met with the foreign consuls in Osaka to guarantee their safety and agreed to honor all existing treaties and arrange for the execution of the Bizen officer held responsible for opening fire on the foreigners in Kobe.

In response, the British dispatched the Irish doctor, William Willis along with the interpreter, Ernest Satow to Kyoto to help in the treatment of men wounded by gunshots at Fushimi-Toba and to gather intelligence. Military surgery was still in its infancy at the time in Japan and bullet wounds were often simply sewn up leaving the victim to die later.

What relevance do the events at Toba-Fushimi still hold for today besides the name on the intersection and the local dry-cleaners? Certainly the last great land battle fought in Kansai proved decisive in shaping the country's modern history.

The new locus of power was centered in the Emperor, who had sent his standards to the men defending the roads into his capital.

New leaders acting in his name launched Japan upon a process of modernization and westernization which would lead within a generation to a confrontation with the same foreign powers whose intervention in Japan's affairs prompted the political crisis and the civil war that erupted in Kansai in 1868.

The violence and bloodshed implicit in the name 'Red Pond' was eventually going to spread and grow into an ocean as Japan emerged as the major military force in Asia over the next half century.