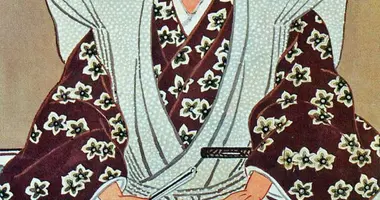

Fukuzawa Yukichi

Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901) 福澤 諭吉

He has been described as the Japanese Voltaire, and compared by others to Benjamin Franklin, and though he is undoubtedly one of the most important and influential thinkers of Japan's modernization period, Fukuzawa Yukichi is not a well known name outside of Japan, which is somewhat surprising, if one considers that almost all visitors to Japan carry around a picture of him in their wallets as his portrait is on the 10,000 yen banknote.

Bust of Fukuzawa Yukichi

Birthplace of Fukuzawa Yukichi

Known as the founder of the prestigious Keio University, and the man who coined the phrases "Civilization and Enlightenment" (bunmei kaika), and "leave Asia, join the West" (datsu-a, nu-o), two of the slogans that drove Japan's modernization program in the Meiji Period.

Fukuzawa Yukichi is variously described as writer, translator, newspaperman, journalist, teacher, educator, entrepreneur, but one thing he never has been called was politician, which probably accounts for why he was largely able to maintain a certain level of integrity.

He was born in 1835 in Osaka, the second son of a low ranking samurai from the Nakatsu Domain, present day Oita Prefecture, who was working at the domain's trading offices in Osaka. Fukuzawa never really knew his father as he died when Yukichi was less than 2 years old, and he was raised by his mother back in Nakatsu.

According to his autobiography, his mother had a great influence on his attitudes, and he especially remembers her benevolence and kindness towards those in the lower classes. He was also deeply resentful of the disdain and discrimination he suffered.

While the class system of Tokugawa Japan is well known, less understood is that within the samurai class itself. There were deep divisions and distinctions between lower ranking samurai and upper ranking samurai.

The family's poverty also meant that he was not able to go to school until the relatively late age of 14, however his father had collected a sizable number of books, so Yukichi was able to study by himself and was therefore able to escape the rigidity of thought that characterized the schools at the time.

In his autobiography, Fukuzawa gives many examples of experiences in his youth that had a bearing on his independent thought, and my own favorite concerns a local Inari shrine. Inside a shrine, usually hidden from view, is a goshintai, a sacred object in which the kami is believed to reside. Often this would have been a rock, as was the case in this shrine.

Local Inari Shrine in Nakatsu where Fukuzawa "experimented" with a rock

What Fukuzawa did was take out the rock and throw it away and replace it with another. He waited for divine retribution, and none came, and laughed to himself at the next festival when all the locals worshiped "his" rock. From then on he had no time for superstition and magic and sought explanations in the real world, and with a lot of emphasis on skepticism and doubt.

In 1853, when Fukuzawa was 19, Commodore Perry arrived in Japan for the first time and made his demands that Japan open up to the West. Fukuzawa was sent to Nagasaki to study Dutch and western gunnery, but only stayed a short time before making his own way to Osaka where he enrolled in the Tekijuku, a school of Dutch Learning and during his three years there studied mostly physics, chemistry and physiology, and of course, Dutch.

In 1858 he was appointed teacher of Dutch to the Nakatsu Domain and moved to Edo (present-day Tokyo). The following year Yokohama opened as a treaty port but upon visiting the foreign settlement Fukuzawa was shocked to discover that Dutch was not the language of the world, rather it was English, so with little more than a Dutch-English dictionary set about the task of learning a new language.

In 1860 he was invited to join the first mission sent by the Shogunate to the USA, and while only there for three weeks he was able to get what he considered his most valuable asset, a Webster's dictionary. On his return he was employed by the government to translate diplomatic documents and in the next year was invited to join a year long mission to Europe.

As with his American trip, he had little interest in the technology and machines on show, as these he could learn about from books, but what fascinated and intrigued him were the social relations and political and economic institutions he encountered. It was while in Europe that he became convinced that the path to success for Japan was not in purchasing technology and armaments, rather in the education of its young and this led to what in Japan nowadays is considered his greatest book, An Encouragement of Learning. His travels also became the basis of Things Western, a series of three books that sold over a quarter of a million copies.

On his return from Europe he refused offers of jobs within the government and instead opened a school that became in time Keio University, and he continued to write prolifically. Much of his writings, like An Encouragement of Learning and Things Western were written for mass audiences, and for this he had to create a completely new style of writing, as in Japan at that time, writing was an extremely formal system belonging to the elite. In a similar vein, public speaking and debate were unknown forms of communication, and he is credited with introducing them into Japan.

Fukuzawa also wrote for fellow academics and intellectuals, and his An Outline of a Theory of Civilization published in 1875 is perhaps his best known of this type of writings. Fukuzawa was never a believer in the total acceptance of all things western, he was quite critical of many moral and spiritual aspects of what he encountered in the west, and he was very much a patriot and nationalist.

He believed that there was much in western ways of thinking that could help to make Japan stronger and able to resist western imperialism, and so he contributed to Japan's own imperialism. It is also possible to see that at times he did not "walk the talk", for instance though he is considered to be the foremost advocate of equality for women at the time, his school never did accept any female students, but his influence on the modernization of Japan was huge. He died at the age of 66 in Tokyo in 1901. His grave is in Azabu-san Zenpuku-ji Temple, Minato ward, Tokyo.

Fukuzawa Residence & Memorial Museum, Nakatsu, Oita Prefecture, Kyushu

Fukuzawa Yukichi's study in Nakatsu, Oita, Kyushu

Fukuzawa Residence & Memorial Museum

The home in Nakatsu that Fukuzawa grew up in until he was 19 is a registered National Cultural Heritage Site and next to it is the Fukuzawa Memorial Museum. The house itself is a fine example of a thatched dwelling but visitors can only peer in, not enter.

In the yard is a storehouse that Fukuzawa himself remodeled to serve as a study space for himself. The Inari shrine that Fukuzawa "experimented" with as a youth is also in the grounds. The museum contains manuscripts, first editions, and other artifacts from Fukuzawa and his period.

Fukuzawa Residence & Memorial Museum

Open every day from 8.30 am to 5 pm.

Entrance fee Adult 400 yen; Children 200 yen

586 Rusui-machi

Nakatsu City

Oita 871 0018

Tel: 0979 25 0063

Books by Fukuzawa Yukichi available in English translation

The Autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa. Trans by Eiichi Kiyooka, Foreword by Albert M. Craig. Columbia University Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-231-13987-8

An Outline of a Theory of Civilization. Trans by David A. Dilworth, G. Cameron Hurst III. Keio University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-4-7664-1560-5

An Encouragement of Learning. Trans. David A. Dilworth. Keio University Press. 2012. ISBN 978-4-7664-1684-8

Text + images by Jake Davies

Book Hotel Accommodation in Tokyo Japan

Books on Japanese History

Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901): read a biography of the Fukuzawa Yukichi the Meiji Period writer, translator, newspaperman, journalist, teacher, educator and entrepreneur.