Western Food in Japan

Western Food in Japan: read a history of the introduction of Western provender in the Japanese kitchen: okonomiyaki, beef, sukiyaki

Western Provender in the Japanese Kitchen

by Alan J. Wiren

nikugyaga or nikujaga (肉じゃが)

nikugyaga or nikujaga (肉じゃが)

Some of the food experiences in store for a visitor to Japan derive from her millenniums old history. Others were inspired by contact with the world outside, but are no less Japanese for that.

It seems whatever passes in over Japan's borders becomes transformed. Shower heads migrate off the walls into our hands, teriyaki burgers are flipping in Japan's McDonald's, and Japanese rappers don't need to make the lyrics rhyme.

Notions and goods from other lands are altered just enough to make them uniquely Japanese, and no less so with the basic ingredients of Western food. Perhaps the two that have been most thoroughly assimilated are wheat flour and beef.

Although wheat was used to supplement rice through most of Japanese history, it gained its niche as a Western commodity with a Japanese twist after two tragic events. In 1923, more that half of the city of Tokyo was destroyed by a major earthquake. The usual lines of food supply were disrupted and prices soared, but wheat flour was an affordable alternative. When the crisis had passed it had left a culinary legacy in a snack called issen youshoku, which roughly translates as "one penny Western food." This popular children's food was a batter of flour and water, spread in a circle on a grill, much like a crepe, scattered with chopped green onions and folded in half.

The Second World War brought nationwide food shortages, and when it was ended in 1945, Japan was desperately in need of aid. Part of that aid came as food supplies, including flour. While accepting the western staff of life, the Japanese did not embrace western recipes along with it. Sandwich bread and flapjacks are not unheard of in modern Japan, but other, thoroughly Japanese, preparations have become far more common.

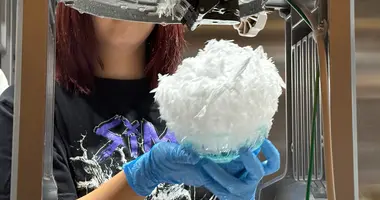

Okonomiyaki (お好み焼き)

Okonomiyaki (お好み焼き)

One, often recommended, culinary curiosity is Okonomiyaki. The name of the dish can be translated as "whatever you like, fried." While this certainly embraces its diversity, it is hardly a succinct description. One restaurant in central Osaka used to describe it, on a large-lettered sign, in English: "Japanese pizza pie or a kind of play food," but in fact, it bears a greater similarity to issen youshoku.

After the war, what was once a child's treat, morphed into a meal. The addition of an egg to the batter made it more substantial. Later as prosperity returned, meat or seafood was added and okonomiyaki became a dish that people of all ages enjoy. Nowadays it is myriad in its variety. Not only do different prefectures take pride in their different styles, but many restaurants serving okonomiyaki as their main fare strive to put their own signature on it.

Hot griddle for okonomiyaki

Hot griddle for okonomiyaki

Whatever part of Japan you find yourself in when you order okonomiyaki, you will probably be sitting in front of a griddle. When your meal arrives, its main components, egg, flour, and other basic ingredients you have chosen will be in a small bowl. You should pick up your chopsticks and mix them well before pouring them out in a circle and adding toppings and seasonings like dried bonito flakes and mayonnaise.

The incorporations of beef into Japanese cuisine are legion and surrounded by myth. The dish called nikujyaga is a fine example. The name translates directly as "meat potato" which certainly smacks of western origin. It is a kind of soup that contains beef (usually thin slices, although ground beef or even ground pork are sometimes used), chunks of potato, onions and often strings of devil's tongue jelly (konnyaku).

If you delve into the origins of this dish, which has become a kind of Japanese comfort food, you are bound to run across the name of Heihachiro Togo, who was a fleet admiral in the Japanese navy in the early 1900's. Togo studied extensively in England and it is often claimed that upon returning to Japan he ordered his cook to create a Japanized version of the beef stew he had enjoyed in the West, thus introducing nikujyaga to Japan via the galleys of her navy.

While Togo gained a reputation in England, both as an outstanding scholar and for a voracious appetite, staff writer Asami Nagai, of the Japanese newspaper The Daily Yomiuri, published an article in February 2000 that quotes the mayors of Maizuru and Kure cities (where Togo was stationed at naval bases after his return), and explains that the connection with Togo is no more than a supposition, promoted to increase tourist trade.

We may not be able to trace the introduction of beef into Japanese cuisine to a single person, but it is clear that the military was one avenue that it did come through. In the late nineteenth century, Tokyo hospitals served beef to injured soldiers, and beef was added to the rations of, first the navy, and then the army as part of a government effort to improve national health. It is not unlikely that both nikujyaga and the Japanese version of curry were first cooked up as military rations.

This all begs the question of why beef needed to be introduced at all. The cow, or ox, after all, was a domesticated animal in Japan long before the nation came in contact with Western culture. The answer is in Japan's history of Buddhism and the religious prohibition on eating meat. Outside the temples, meat was almost never completely excluded from the diet, but beef was never the flesh of choice. If eaten at all, it was considered a medicinal aid, or a tonic to ward off ill health.

At the turn of the twentieth century an emerging attitude equating modernization with westernization helped to bring dishes like beef stew into restaurants in the cities. In rural, farming areas, on the other hand, cattle were kept as workmates on the farm and often regarded as near family members.

When beef insinuated into this part of Japanese society, it was more often in the form of what is now known the world over as sukiyaki. While incorporating thinly sliced beef, this dish includes more vegetables than nikujyaga. It is simmered in a shallow pan to create a savory sauce, rather than in a deeper pot of broth, and the bulk of nutrition is often provided by tofu or a final course of noodles simmered in the sauce infused with all the previous ingredients.

Yaki, as in okonomiyaki, means "fried". The ideograph used to write Suki is the Japanese word for "hoe" or "plow". Stories explaining origin of the name sukiyaki abound. One involves a peasant polished his plow to cook the meat a nobleman brought in from the hunt. Another credits the Portuguese in Japan with a desire for meat so insatiable they would eat it from the backs of their own plowshares. Some authorities (e.g. Merriam Webster) claim that suki derives from a different word, with a similar sound that means "thinly sliced."

It is a fact that when sukiyaki was prepared at countryside homes in days gone by, it was often cooked outdoors in order not to offend the ancestors by grilling meat in front of their altars. In that circumstance alternative cookware was likely used rather than tainting the everyday pans. If you like the more primitive imagery, rest assured you can find restaurants in Japan that serve sukiyaki with a sizzle platter shaped like a hoe, complete with a wooden handle.

Text and Photos by Alan Wiren