Waribashi Chopsticks

Read an article on The Waribashi Conundrum: Japan and the use of disposable chopsticks.

The Waribashi Conundrum: Disposable Chopsticks in Japan 割り箸

by Jiro Taylor

I can't be the only person puzzled by the waribashi conundrum. Every year, Japan gets through roughly 24 billion pairs of disposable chopsticks. That's 185 pairs for every person in Japan. What began as thrifty way to use up wood scraps in the 1870's has spiraled out of control into a fiendish national habit.

There is no established recycling system, so the waribashi are mostly used once and discarded, to be incinerated with other burnable rubbish. The waste is baffling, but even more so when we consider that this is the Japanese doing such squandering.

Japan is famous for its thrift, as much as the modern United States is notorious for its waste. Since ancient times, Japan has confronted its meager natural resources and island isolation head on, attacking its shortcomings with thrift and prudence.

Somewhere deep in the past, the thrift of necessity fused with a moral and spiritual sense of thrift expounded by Shinto, which came to pervade all spheres of Japanese life. Japanese-American art professor, T. Kaori Kitao writes: "In our Japanese way of thinking, wasting is not just wasting. It is an offense against the beneficent deity and it comes closest to the Christian notion of sin."

Japanese Thrift

Being brought up by a Japanese mother I had firsthand experience with the Japanese abhorrence of waste and love of thrift. Spotting bargains

like half price lettuce and two-for-one cabbage's at the local supermarket is a late night hobby for my mother, and throwing out old, unused items of furniture or clothing remains unthinkable. And yes, we did use waribashi, but we washed them and used them over and over again, until the wood went mushy or they broke in our hands. Like many of her post-war generation who learned not to waste during the lean times, my mother is a thrift

expert.

Japan still remains in many ways a nation of thrift experts, and this is what makes the waribashi conundrum such a puzzle.

Every foreigner who has lived in Japan has done battle with municipal waste disposal systems, and noticed the nationwide obsession with recycling. Disposing of trash in Japan is a laborious process, but one that ensures the absolute minimum of waste.

Furthermore, Japan is a world leader in thrifty cars. Kei cars with their mini, eco-friendly 0.66 liter engines are as ubiquitous in Japan as gas-guzzling 4x4 SUV's are in America.

In recent years, Japan has changed its ways to become a world leader in industrial energy efficiency technology and pollution controls, and

Japan's per capita energy consumption is about half that of the United States. Japan is a leading authority on non-polluting renewable energy sources such as wind power, solar power and geothermal electricity, and has even learned how to turn common trash into energy.

Using the new-fangled Plasma Torch Technology, the Hitachi Metals plasma plant in Utashinai City, Hokkaido produced 8 megawatts of power by torching auto waste in 2002. If that's not proof enough of Japanese thrift, then consider this: their toilets are the most efficient in the world. The "Neorest" toilet, built by Todo Ltd., not only comes with a seat warmer, air-deodorizer, bidet and an automatically lifting seat, it uses a mere 1.2 gallons per flush, six times less than the average American toilet.

In this nation of moral, spiritual, eco, industrial and practical thrift, the wastage of waribashi is all the more mystifying. If Japanese are so wary of waste, what is the reason behind the squander of 63 million pairs of chopsticks per day?

Yuki Komiyama, former president of the Canadian Chopstick Manufacturing Company, owned by the monolithic Mitsubishi Corporation, argues that Japanese just "don't want a chopstick that is used by someone else ", because according to traditional Japanese belief, chopsticks are "given by the gods."

Shinto & Chopsticks

Shinto belief maintains that hashi (chopsticks), are a sacred bridge between humans and the gods. Thus, in Shinto ceremonies of birth, marriage and death they play a special symbolic role. Moreover, the Shinto faith is heavily laden with the themes of purity and renewal, which are evident in every crack of virgin waribashi.

If Shinto is to be the great redeemer of waribashi, some startling ironies need mentioning. Firstly, there is the Shinto doctrine of thrift: Wasting is sinning. Secondly, there is the Shinto reverence of nature. "Love of Nature " is one of the "Four Affirmations" of Shinto belief, which is heavily based upon the veneration of and harmonious coexistence with the natural world.

The Shinto respect of nature trickles down to the core of Japanese society and mentality, and can be seen in the arts of ikebana, bonsai, architecture, garden design and the quirky Japanese observance of seasonal changes and cherry blossom blooming. The production and waste of waribashi directly oppose the Shinto creed. Forests around the world, (though not in Japan), have been irreparably damaged by the waribashi business.

Chopstick Art

When it comes to waribashi, what happens to Shinto thrift and reverence for nature? Donna Keiko Ozawa, a third generation Japanese-American artist, points out that waribashi "are so pervasive in Japanese culture, they are rendered invisible."

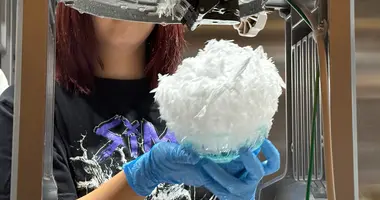

In 1993, Ozawa spent a month in Tokyo working on an art project designed to highlight the waribashi problem. Ozawa collected over 15,000 used waribashi from small noodle shops in Tokyo, washed them and created a sculpture entitled "tsuyu (Rainy Season)".

She recorded the opinions of restaurant owners and other users, and found that many people were unaware of the environmental problems contributed to by waribashi. For many Japanese, they are just a part of daily life and the environmental issues are unknown. Moreover, waribashi have become so ingrained into society that to refuse them would be to run against the social current. In a culture of conformity and a society which favors hammering down the nail that sticks up, opposition to waribashi has been predictably low key.

For the immediate future, it is likely that the pervasiveness of waribashi in Japanese society will only increase. Shinto reverence of nature wanes a little with each new generation, while a newer culture of convenience blossoms.

The ancient Japanese ideal of thrift is eaten away by modern production techniques and a growing "throw-away" consumer culture. The fight against waribashi is expanding but it will take time and government measures to really stamp out the practice. In the meantime do your part: spread the word and use as few waribashi as you possibly can.

Japan Articles by Jiro Taylor

Read more about chopsticks in Japan