Seaweed in Japan

Nori Seaweed: read a feature on seaweed (nori) in the Japanese diet and the health benefits of seaweed and laver.

Seaweed in the Japanese diet - Essence and Accents from the Sea

by Alan Wiren

From the dawn of civilization, Japanese women would gather seaweed in the morning and burn it in the evening.

On the surface it seems like busy work or vengeance, but it was actually a life-giving practice. It hardly sounds appealing, but one of the earliest uses for seaweed, in Japan, was to extract its salt by drying it in the sun, then burning it and using the ashes to season food.

Thankfully, since then, the paths of table salt and seaweed, in Japan, have separated. The Japanese found better ways of taking salt from sea water, and more delectable ways to include the nutrient-rich vegetables from the sea in their diet. The influence of Buddhism helped them on the way.

Buddhism & Vegetarianism in Japan

Buddhism introduced a vegetarian diet to Japan and, because oil was virtually absent from the early Japanese kitchen, neither pan frying or deep frying were used. Boiling was the nearly universal cooking method in Japanese temples, and it became common practice to add a piece of giant kelp -- konbu (or kombu) in Japanese -- to the broth.

Ikura sushi wrapped in nori

Konbu, as would any edible seaweed, added salt and calcium (an essential nutrient that most of us do not get enough of) to the monks' diet.

More saliently, konbu contains glutamine, the natural form of monosodium glutamate, which enhances the flavor of any foods that are cooked with it.

Used on its own, or (for vegetarian dishes) augmented with the water used to soak dried shiitake mushrooms, or flavored with flakes of dried bonito, konbu stock became a signature element of both modern and traditional Japanese cuisine. In Japanese it has been given the name, dashi.

Shizuo Tsuji, founder of the Tsuji Cooking School, wrote in his book, Japanese Cooking A Simple Art, "Dashi provides Japanese cuisine with its characteristic flavor, and it can be said without exaggeration that the success or failure (or mediocrity) of a dish is ultimately determined by the flavor and quality of the dashi that seasons it." In addition to making this fundamental contribution to Japanese cuisine, konbu can be eaten on its own cut into thin ribbons or shreds. Small pieces of rolled up konbu are a traditional part of Japanese New Year meals.

Wakame

Another kind of kelp, very popular in Japanese cooking, is called wakame. Wakame has a thinner leaf than konbu, a sweeter, less forthright flavor, and a silkier texture. Both kinds of kelp are a common ingredient in Japanese soups. Wakame often makes an appearance in salads.

Hijiki is a different, well liked, species. Unlike the broad leafed kelps, hiijiki has threadlike branches. It has a slightly nutty taste and is usually simmered with soy sauce and other elements, taking on their flavor. Unlike most other seaweeds, it is over fifty percent carbohydrate.

Hijiki is also said to help eliminate toxins from the body, but this has recently become a point of controversy. The food standards agencies of several countries have tested their hijiki products and found they contained high levels of inorganic arsenic. The evidence suggests that it does not matter where the hijiki grows, because the levels of arsenic found were similar in all countries. Those agencies have issued warnings recommending against eating hijiki.

On the other hand, hijiki is usually served in small quantities, as an accent, an appetizer, or one ingredient in a salad, soup, or rice dish.

In order to receive a harmful dose of inorganic arsenic from hijiki, you would have to consume large quatities of hijiki every day for an extended period of time.

Notwithstanding their caveats against eating hijiki, the food standards agencies also state that no one who has been eating normal amounts of hijiki up until now should consider themselves at risk, and that no other edible seaweeds contain high levels of inorganic arsenic.

Nori

Nori is a seaweed that has found a solid niche in Japanese cuisine. It was the first to be farmed in Japan. When the Tokugawa Ieyasu established his shogunate in what is present-day Tokyo in the early seventeenth century, he ordered local fishermen to bring fresh fish to his palace every day. To make the task easier, the fishermen of the Tokyo Bay area built a bamboo fence in the bay to enclose an area where fish could be held. They soon discovered that nori grew abundantly on this fence. By early in the next century, there were 142 nori beds being maintained in the bay.

While the Western world has historically ignored the nutritional benefits of most seaweeds, nori has been eaten by the native peoples of countries around the globe. Dry nori is between thirty and fifty percent protein, and high in fiber. It has a crisp texture and a sweet, slightly salty taste, even though its sodium content is relatively low.

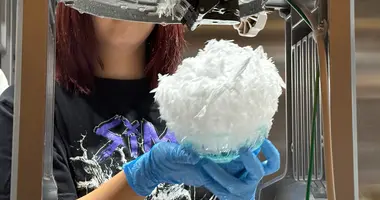

In its natural form, nori is a very thin-leafed, reddish-colored plant (called "purple laver" in English), but virtually all nori sold in Japan is processed by cutting it into small pieces and making a slurry that is dried on frames similar to the ones used to make paper. The uniform sheets, which turn a dark green color during processing, are the product you will find in Japanese food stores.

In restaurants, you will find nori wrapped around sushi or balls of rice (onigiri). Convenience stores in Japan sell onigiri in special packages that keep the dry nori separate from the rice until the moment you open them so that the nori retains its crispness.

A common nori treat is to lay a small rectangle on top of a bowl of rice, then use chopsticks to wrap the nori around a little of the rice before popping it into your mouth. Thinly cut slivers are used as a garnish for noodles or rice.

Any Japanese restaurant experience is bound to include the flavors and nutrition of some kind of seaweed. If you want to try some recipes including seaweeds on your own, you will find any of the many seaweed varieties in supermarkets and basement floor of department stores. Remember there are several different grades of konbu, but the recommendations (for using it on its own, making dashi, or for both) are usually listed on the package.

Finally, it may be of interest to know that since 1966 Japan has had a "Purple Laver (Nori) Day": February 6, initiated by the National Federation of Laver, Shellfish and Fishing Industry Co-operative Associations.

It harks back to an edict issued on that date in the second year of the Taiho era (701 AD) when nori was designated as one of the varieties of marine produce required to be paid as tribute tax.

This is the earliest record of the importance of nori's place in the Japanese diet and has thus been marked as a commemorative event.