Tea in Japan

Japanese Tea: read a feature on the history and political/cultural significance of tea in Japan through the ages.

The story of tea in Japan 茶

by Alan Wiren

Tea likes to grow in misty mornings and afternoons. It likes rolling hills and a slightly acid soil. When the High Priest Myoe was given some tea seeds brought from China to Japan in the late twelfth century, he looked for just such a place to raise the plants.

Myoe lived in Kyoto, so he did not have to go far. He found all these things in Uji. He transplanted his tea seedlings there and began promoting the drinking of tea throughout Japan.

Tea has affected the history and economy of the world like no other beverage. While Japan did not enter the mainstream of worldwide tea trade until relatively recent times, tea did infuse itself into Japan's early economy and politics, in just the same way as it did elsewhere.

Well, almost the same. As with many other things they have imported, the Japanese adapted the production of tea to their own taste. The Chinese were the first to produce green tea, and still do. However, the teas that became popular in most other parts of the world were black teas.

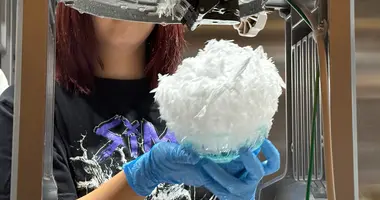

Making tea ready for the pot is a complicated process. After tea leaves are picked and dried, in the case of black tea, they are allowed to ferment for a time, which darkens them. To produce green tea, the Chinese traditionally let the leaves wither, and pan-fried them. The Japanese, however, took up the practice of steaming the dried leaves, which gives the leaves a brighter green hue. Also, whereas the Chinese shaped the green tea leaves usually into a ball, the Japanese pulverized them to create a powder known as matcha. And that is what you will find, still being produced and sold in Uji, today.

Japanese tea production in Uji

Uji has remained a constant center of tea production for over eight hundred years, even during times of civil war and shifting seats of government, which caused relocation of other agricultural and industrial centers. Uji's favorable soil and climate were important factors, but not the only ones.

Uji was in a good position to supply the imperial court in Kyoto, and later, Toyotomi Hideyoshi's government, centered on Osaka Castle. But during the time that Hideyoshi was coming to power, Uji found another friend that would keep her in favor after Hideyoshi's house had fallen. When Tokugawa Ieyasu, temporarily in defeat, retreated through the village of Uji, he was helped by a tea merchant by the name of Kanbayashi. When Tokugawa came to power, not only was Kanbayashi mayor of Uji, but his family were named the official suppliers of tea to the shogunate.

The capital of Japan moved to present day Tokyo, but when it came to tea, the capital came to Uji. Every year great empty jars were loaded into palanquins which were lifted to shoulders, and surrounded by soldiers to make the trip from the Shogun's palace to the Kanbayashi tea shop in Uji where they were filled with tea of the finest grade and sealed in the most correct and formal way.

They were then packed up and marched back to the palace in Tokyo. The Tea Container Procession was given the greatest reverence and respect all along its route. Even now, Uji reenacts part of that procession every year in April.

When the Tokugawa period ended and the authority in the land was returned to the emperor, a change came about in tea drinking, too.

The tea ceremony that centered on preparing a cup of matcha powdered green tea had become associated with the Shogunate and thereby quickly fell out of fashion. That could well have spelt misfortune for Uji, as well, but for a sudden change of heart in a Buddhist monk who lived nearby.

At over sixty years of age, Nagatani Sannojo decided to become a tea merchant. He created a new style of tea ceremony using the recently developed sencha: green tea leaves rolled into needle-like points. The sencha tea ceremony became popular and ensured Uji's economic survival until another turn in public sentiment brought back the popularity of the matcha tea ceremony.

Uji Today

Uji, today, is a charming, laid-back tourist town. You catch the scent of green tea in the air as soon as you step out of Uji station. Near the exit a post box is made up to look like a large tea container, making a fun backdrop for the obligatory photo. On the same side of the exit is the Tourist Information Center where you can pick up a sightseeing map.

Heading away from the station, you will come to the front of a traditional building stretching along a street dotted with other well preserved houses. It is the main branch of a very old tea vendor. Turn left here, and you will soon find the Kanbayashi Tea House.

The top two floors of this building display the ancient tools that were used to harvest and process tea in Uji City, as well as the mills for grinding matcha.

There is a section of an old tea tree preserved there under a curiously constructed skylight. Built out from the wall, in the style of a dormer, this type of skylight provided a constant level of illumination throughout the day in places where tea was sorted and graded by hand in the days before domestic electricity.

Sen no Rikyu & Japanese tea

There are hand drawn scrolls that show the process of making tea from harvesting to the pot, and others that show the Tea Container Procession. There is a statue of the fourth mayor of Uji, who died while fighting under his own banner that bore the Chinese character for "tea", along with a story about how he was once visited by the time-honored master of tea ceremony, Sen no Rikyu.

The story says that the presence of Rikyu so agitated the mayor that he dropped the utensils, and fumbled the tea ceremony quite badly, but that Rikyu praised it as the best he had ever attended. When asked why, Rikyu explained that never had it been more obvious how much the host cared about the comfort of his guest.

At the end of the street you will come to the wide Uji River, spanned in several places by red, arched bridges whose posts are capped with copper points, gone green with age. Here is the beginning of Byodoin-Omotesando, a small arc that swings out from the river bank. The smell of roasting tea is a presence along this stone-lined street. It hosts dozens of tea shops, and restaurants that sell refreshing green noodles and green iced milk, flavored with matcha. Kanbayashi's main store is here with another, smaller museum on an upper floor that has a model of the Tea Container Procession.

There are plenty of opportunities in Uji to take part as a guest in the matcha tea ceremony. The third floor of the Konbayashi store is a "tea house" where you can make such a reservation. Nearby on the street that runs parallel to the river is Taiho-An, run by the Uji City Tourist Information Center next door.

Taiho-An is more in keeping with master Rikyu's style, with modest bamboo construction, a small garden, and a gong that you ring to announce your presence. On the other side of the river, the Kyoto Prefectural Government runs a tea house that sometimes offers free samples of tea out in front of the building for those in a less formal mood.

Of course, if you'd rather avoid the prescriptions and formalities that come with the drinking of tea, there's nothing stopping you from dropping in to any supermarket or specialist tea store and choosing from the selection on display there. As with black tea, boiling water and a cup are all you need to partake in your own way in a ritual that both refreshes and relaxes.