Japan's Traditional Food Styles

Japan's Traditional Food Styles: read an article on Japan's traditional food styles including kaiseki ryori and shojin ryori.

Japan's Traditional Food Styles 懐石料理

by Alan J. Wiren

A visitor to Japan can expect a wealth of enjoyment from her traditional food. The presentation and flavors alone are a delight, but understanding the origins of what is at the end of your chopsticks can give a deeper appreciation of the food and a greater understanding of the society that brought it there.

Looking back one thousand years you would see tribute flowing, from all parts of the nation, to Kyoto, the ancient capital; to the emperor, the ultimate power.

Fish, rice, salt, and firewood traveled over well established routes to the palace kitchens where they met with local ingredients to become the sustenance the imperial court.

The food was served, to those fortunate enough to be members or guests, on trays with four short legs, called zen. A meal could comprise several courses and each diner would receive one zen for each course. Each course consisted of several dishes.

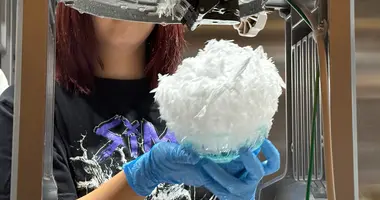

Japanese full course kaiseki dinner

Japanese full course kaiseki dinner

Fried tofu course of a kaiseki dinner

Fried tofu course of a kaiseki dinner

Japanese Court Food

It might seem to go without saying that, as in modern times, the focus of these courtly meals was flavor and nutrition, but those are not universal objectives in food history, and in Japan, times were about to change. The ninth to the twelfth centuries saw a shift in power. The emperor gradually became a figurehead and real power was taken by the samurai class.

What happens to food between the field and table has, throughout history, paralleled the development of the social classes for whom it is destined. The substance of Japan's imperial banquets transformed along with the political climate. Court meals became affairs meant more to impress, than to nourish. Trays were filled with more food than could be eaten in a sitting, with many dishes meant to be appreciated with the eye rather than with any other organ.

Food for the Samurai

Meanwhile, the samurai had come to power from the peasant class. Theirs was a vastly different lifestyle from the imperial family's that made for meals without frills, often without flatware. While people of the court used spoons, the food of the common people was served in bowls and eaten with hands. Chopsticks would not appear until later. As their wealth and power increased, some samurai did begin to adopt the court banquet style, but when the military government was officially established and the first Shogun took office in the thirteenth century, those who had were punished.

Although the Spartanism, delineating shogunate from court, would not last, differences at the table that distinguished their social classes would flourish. As the samurai became more firmly established, and built palaces of their own in Kyoto, two different schools of cooking grew up alongside the two branches of government. The Shijou school was for nobility and the Ouska school was for samurai. Both were ostentatious, and served their elaborate fare on the four-legged trays that give this style the name of honzen ryori. As time went on, they would create more and more elaborate rules of food preparation that distinguished one from the other.

In time, the shogunate, lost their power of rule to the lords who governed their lands, but his did nothing to hinder the trend toward flaunting wealth and social status at dinnertime. This nearly completes the backdrop against which a very different, and perhaps the most well known, style of Japanese cuisine was about to appear. Only one more element is needed.

Japanese Tea Ceremony

By the sixteenth century, tea had become a popular drink among Japan's nobility and samurai. The samurai often practiced tea drinking as a kind of competition. Samples were served to banquet guests, and the contest was to identify them by tasting. Such games were often followed by much appreciation of sake. At this time a man appeared who would open a new chapter in food history: a Buddhist monk who would become tea master to two of the three military leaders who reunified Japan under the rule of the Shogunate. His name was Sen No Rikyu.

It was Rikyu who crystallized the form of the Japanese tea ceremony. A contrast to the embellished banquets of the upper classes, his was the way of simplicity and harmony: harmony between the guests, and with the natural world around them. Rikyu was respectful of the powerful effect that tea was considered to have on both body and mind, and to mollify it he prescribed a light meal an essential part of the ceremony. The philosophy behind that meal still survives in the kaiseki ryori style of dining.

Kaiseki Ryori

In this context, it is easy to see why the name kaiseki was chosen. It refers to a warm (kai) stone (seki) that monks would slip into their robes, against their bellies to ward off hunger pangs during devotions. Rikyu's ideal repast was one that did not call attention to itself, rather it was integral to a heightened appreciation of the moment.

Nowadays service called honzen and kaiseki can be had in Japan's restaurants, but since Rikyu's day times have continued to change, and both of these food styles have changed with them. Perhaps the greatest influence was the evolution of the restaurant, itself. It wasn't until nearly a century after Rikyu's death that food service outside the Japanese home moved from the teahouses and inns that provided refreshment along the roads for those obliged to travel, into the cities.

When it came to serving honzen and kaiseki ryori the new restaurateurs were faced with challenges. When the honzen style was served in a restaurant, economic pressure dictated that the fare must not be only visually aesthetic, but nourish the diner, as well. In the case of kaiseki few customers would pay the inflated costs of restaurant dining only to be presented with Rikyu's charming, but austere ideal.

The main influence of restaurants on honzen and kaiseki ryori has been to make them more similar to each other. While honzen became more practical, kaiseki became more presentation oriented. What still distinguishes them is that honzen is still a banquet style meal, with small courses that follow one after the other, some prepared with elaborate technique, while kaiseki is still a selection and presentation in harmony with the natural world. If you really want to experience the kaiseki ryori of Rikyu's day, look for cha-kaiseki.

Shoujin Ryori

One style of Japanese food presentation that has remained relatively untouched by time is shoujin ryori. Shoujin can be translated as "devotional" because this is the style that has been handed down in Buddhist monasteries and temples through hundreds of years. Of course it is strictly vegetarian, but the lack of meat by no means makes it dull. It is also a style in harmony with the seasons, and accommodates variety and ingenuity that make this kind of meal an entertainment on its own.

Another constant in the history of traditional Japanese food is the city of Kyoto. While the seat of the nation's political power has shifted multiple times, Kyoto has remained a living repository for the styles that comprise her culinary past and present. Kyoto's Nanzenji Temple is famous for offering shoujin ryori, and has a tradition of doing so for the last three hundred years. While Kyoto hosts countless restaurants that offer some interpretation of the kaiseki style, Yamabana Heihachi Jaya, next to the river Takanogawa, has a history nearly as long as the city's own, and serves meals in both the honzen and kaiseki styles.

Yamabana Heihachi Jaya is a five minute by taxi ride from the Kitayama Subway Station. See their website for directions.

Nanzenji is on the Tozai Subway Line. From Keage Station, cross the street and go through a brick-lined tunnel. The temple is a 10 minute walk in the same direction.

Text and Photos by Alan Wiren