Ebisu and Daikoku

Ebisu and Daikoku. Read a history and description of Japan's happy divine couple, the gods Ebisu and Daikoku, gods of plenty.

Ebisu and Daikoku: Bringing Home the Bounty 戎大黒

by Alan Wiren

No one could bring better fortune or serve as a more fitting keepsake of Japanese memories than Ebisu and Daikoku: a jovial pair of gods.

In Japan there are train stations, streets, bridges, even city districts, that bear their names.

Ebisu and Daikoku are inextricably woven into the fabric of the culture. Thousands of shrines throughout the land are dedicated to them, and their images crop up in businesses and homes.

Being the gods of bounty, providers and protectors of the food stores, and the patron deities of merchants, Ebisu and Daikoku hear the prayers of both housekeepers and traders.

The stories of Ebisu and Daikoku are two threads in the tangled skein of Japanese mythology.

Some Japanese will tell you they are Shinto when they are born, Christian when they marry, and Buddhist when they die.

Generalizations aren't always helpful in understanding a culture, but this one effectively illustrates the diversity of the traditions that have come together to characterize spiritual life in modern Japan.

Ebisu

One reason why Ebisu is so popular may be because he is purely Japanese. He appears very early on in the Japanese creation story, the Kojiki, at the beginning of which two gods are charged with the task of begetting the world (starting and ending, of course, with the Japanese archipelago).

Stone statue of Ebisu, Kyushu

Stone statue of Ebisu, Kyushu

These two gods descend from the heavens and set to their task in earnest -- only to discover that they have gone about it wrongly. When their first offspring arrives, he is a child without bones (and without arms or legs, in some versions of the story).

They call him Hiruko - 'Leech Child'. Even after Hiruko reaches the age of two, he is still unable to stand up, and his parents, admitting failure, put him into a boat of reeds and "let him float away."

Hiruko's parents eventually learn how to procreate properly and his mother goes on to give birth to all the islands of Japan, and then to the multitude of gods who were its original inhabitants. We hear no more of Hiruko in the Kojiki, but his story continues in other legends.

In one popular version, Hiruko's boat of reeds washes up at a fishing village of the northernmost island, Hokkaido.

The Leech Child is found by Ebisu Saburo who takes him in and raises him amongst the Ainu, the native people of Japan. Other versions have him alighting far, far southwest of Hokkaido in Nishinomiya, near Kobe.

Present day Hokkaido asserts its claim with its Mt. Ebisu, and Nishinomiya with its with Nishinomiya Shrine, the principal Ebisu shrine in Japan. Had Hiruko's original parents been a bit more patient, things might have turned out differently, because by the age of three, he develops the bones (or grows the body parts) he was missing at birth.

Ebisu, as an adult, is a beaming, roly-poly character, protector of those who fish and of those who trade. He often carries a fishing rod, or has a big fish tucked under his arm.

Daikoku

Daikoku's lineage is not as pure. Both Ebisu and Daikoku are often portrayed as members of a larger group comprising seven gods of good fortune (Shichifukujin). Aside from Ebisu, these gods followed paths that began in different lands before bringing them to Japan.

Daikoku originated in India, where he was known as Mahakata: a fierce, female warrior. Mahakata made her way to China where, because of her military prowess, she took on the task of guarding the food supplies in Buddhist temples. Her image was often displayed in the kitchens of Chinese Buddhist temples.

One of the 7 Lucky Gods, Shichifukujin, of Japan, Daikoku is strongly associated with wealth

One of the 7 Lucky Gods, Shichifukujin, of Japan, Daikoku is strongly associated with wealth

A wooden statue of Daikoku with his magic hammer

A wooden statue of Daikoku with his magic hammer

When Buddhism came to Japan, it brought Mahakata along with it. Mahakata underwent a huge transformation in joining the Japanese pantheon as the distinctly male Daikoku.

While retaining the association with food, particularly grain, not only was Mahakata's sex changed, but her martial ferocity was turned inside out to become benevolent generosity.

A stone carved Daikoku

A stone carved Daikoku

Daikoku became identified with an important character in the Kojiki, who serves as the foundation for this new personality. The deity's first task in life, after having been born into a family of eighty other brother deities, was to serve as porter.

Daikoku's brothers all took it, simultaneously, into their heads to marry a certain princess, and took off together, to find and propose to her. They put the travel bag on the back of our hero. That bag slung over his shoulder is now one of Daikoku's most well known accoutrements, although the modern-day Daikoku's sack is no longer mere luggage, but brimming with riches and treasure.

To continue the original story, on their way to seeking the princess, the eighty gods find a rabbit who has been stripped of its fur. They make mischief by "advising" the rabbit to bathe in the ocean, then lie on top of a windy mountain. Taking this cruel "advice" the rabbit's skin splits all over, and when the hero (coming along last bearing the bag) finds it, the rabbit is weeping in pain. He demonstrates his compassion by telling the rabbit how to heal itself and restore its fur.

The rabbit has not survived as a companion of Daikoku, but there is another animal who has. The deity in the Kojiki goes on to have other adventures, in one of which he is the object of an attack by the lord of the underworld using divine fire.

Just when there appears to be no hope, he is saved by a mouse who allows him to hide in its hole, while the fire passes above.

Mice and rats are commonly found around granaries, and the rat is a common element in folk tales told about Daikoku. His sack may well be bulging with rice, and he is usually portrayed standing on bales of rice, with a rat often part of the tableau.

In coming to Japan, Daikoku, like Ebisu, gained quite a bit of weight, and was given a hammer. No utilitarian item, this hammer looks more like a big drum with a handle attached. It is an implement of magic which grants wishes, spills out coins when shaken, or sparks off good fortune whenever it gently touches our plane of existence.

With Ebisu bringing fish and Daikoku bringing grain, they had the gamut of food covered in Japan's liberally vegetarian culture of the past, and they were both benign protectors and givers of prosperity.

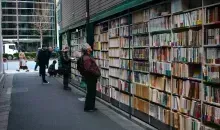

Daikoku and Ebisu carvings in a Japanese flea market

Daikoku and Ebisu carvings in a Japanese flea market

Both Daikoku and Ebisu feature the fulsome belly of plenty as well as the exaggeratedly fat earlobes that are symbols of wealth. They have been worshipped as a pair since the middle of the Muromachi era, and some traditions even have it that Daikoku is Ebisu's father - others that they are brothers.

As benefactors and guardians of the good life, these gods are the focus of gratitude. Their shrines are crowded during the New Year season in Japan by worshippers paying their respects, and their tithes, and praying for Ebisu and Daikoku to watch over them in the year to come, and the paramount shrine to them in Nishinomiya resounds with the western Japan dialect's version of 'thank you': okini, and further east the more standard arigato!

Daikoku

Daikoku